At short notice we decided to go. I referred to the website for this national trail and quickly booked the accommodation we could find along the way, starting on a Monday from Cresswell where the Tyne properly becomes the North Sea. Then I ordered what I assumed would be the corresponding book – but it turns out there are two, and the one I bought was different. I think this was very fortunate and I’m going to tell you about it, including notes on getting vegan food.

Roland Tarr, currently a Councillor in Dorset, has written one of the best guides to a national trail I’ve come across. His enthusiasm for geology, nature, history, engineering, industry and the people of the region brings the landscape to life. A solicitous guide, he manages expectations, attends to hunger, fatigue and doubt, and prompts a more appreciative look at some unpromising sections along the way. The book fit into the leg pocket of my new walking trousers and I referred to it often. It helped us interpret the landscape and took us to overlooked parts of heavily touristed places like Newcastle, Lindisfarne and Berwick-Upon-Tweed. Unlike the website, the book guides readers around Newcastle and then proceeds to the mouth of the Tyne before arriving at Cresswell to pick up the official route and beyond to St Abbs Head in Scotland. So we changed our plans to start in Newcastle, arriving by train on a Saturday evening in late July.

Day 1 Newcastle

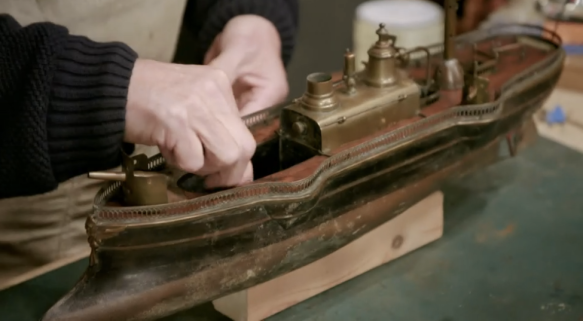

Roland Tarr’s book includes a circular walk around Newcastle and Gateshead. In a masterstroke he specifically takes you to the model above, which is part of ‘The Story of the Tyne’ exhibition in the Discovery Museum – because, he writes,

“When you see a derelict shipyard or factory by the Tyne or a closed railway or coal mine site in one of the coastal small towns and villages, you will understand its importance in the historical order of things instead of just seeing dead and unused structures. You will be able to picture it as it was in the past.”

What a legend – and thank you Newcastle because entry to this museum hasn’t always been free. He took us to the New Castle, the Philosophical and Literary Society which catalysed the inventions of the industrial revolution, over the historical High Level Bridge, under the Tyne Bridge with its kittiwake colony, through the Sage, to the Baltic and the Gateshead Millenium Bridge which we were fortunate to watch tilt open moments after we crossed.

Newcastle that first night was a primal confluence of the races, Pride, and the wedding season. Accommodation was short and we stayed at Jury’s Inn near the station. Some youth football teams down from Scotland for a tournament were playing a stalking and pursuit game in the stairwells far into the night, sabotaging their opponents by pressing all the buttons in all the lifts. Their parents, drinking in peace in the bar, had bullied the staff into not intervening. We ate a very good Eritrean dinner at Mosob Gesana and went off for a wander through the seething streets, carpeted with broken glass just like home. One of the young race-goers I had seen earlier navigating the cobbles near the castle in four-inch heels appeared in our hotel lift and remarked (as the doors opened at empty floor after empty floor) “I wish I could tell you that it isn’t usually like this on a weekend but it totally is”.

On our first morning the streets soon filled with queasy trudging and trundle suitcases, and we saw grandad-aged men supporting each other while vomiting. We put this behind us and had an excellent vegan cooked breakfast at the Supernatural Kitchen which lasted us until dinner, picked up some supplies and followed the walking tour mentioned above. Dinner was competent veggie burgers in The Maven, preceded by a beer in the fairly spacious Split Chimp micropub (I don’t know what a micropub is, only a microbrewery). Also of note, the Jury’s Inn rooms were really quite bad – we had to swap because of a broken window. I sometimes wonder whether we get treated badly because we look like itinerants but the receptionist was enthusiastic about the coast path so maybe it’s just a run-down hotel in a country on the turn.

Day 2 Blyth to Ellington

That second night in Newcastle there was a crash or apprehension on the A1 ( the main view from our window) and the traffic stopped but the sirens and lights didn’t. The following morning we bought an early vegan sausage sandwich from Greggs (too sweet, too dry, £2) and got on the commuter bus down the Tyne through one of the largest business parks I’ve ever seen. Because of the haste in planning, we had to miss out the section between Newcastle and Blyth. Instead we picked up lunch at Morrisons and set off along the River Blyth (where M saw a leaping fish) to cross upstream at Bedlington Station where it briefly rained. No complaints from us about the weather – we’ve seen a drought, 40° and wildfires in Essex this summer – but I couldn’t help making the connection between that and this coal country. The aluminium smelting plant at Lynemouth consumed one million tonnes of coal a year in its day. But now British Volt is at Blyth making battery technology to store green energy – that’s 3000 green jobs with more in the supply chain.

We crossed the East Sleek Burn and returned to the coast and onto the dunes for the first time. We had our lunch of rolls, falafels and salad looking out to sea at the mining village of Cambois (legacy of the Norman Conquest, pronounced Kemiss).

Then it began to rain quite hard so we retreated to the comfortable sofas of Charltons. Then along the A189 for a while to cross the Wansbeck in steady rain, briefly lost in a friendly caravan park and wetly into Newbiggin-by-the-Sea with its enigmatic Sea Couple and Land Couple. A coal seam opens onto the beach at Newbiggin and there is sea coal on the sand. That day we stopped early at the Newbiggin Maritime Centre because M’s recovering knee had reached the end. We called a taxi for the last few miles to The Plough in Ellington and had a wide-ranging conversation with the driver including the cost of living crisis – he had converted his car to LPG and was saving 40%. Meanwhile BP recorded a £6.9bn profit between April and June this year, and Shell also had record-breaking profits – a direct result of domestic energy bills soaring to £3.5k this winter. Unless the next Prime Minister intervenes I can only guess what will happen.

The rain had cleared by the time we left our room to limp round the tidy little village and look at Ellington Pond Nature reserve. Then dinner at the Plough, a Punch Tavern with vegan stuff on the menu. Good night’s sleep.

Day 3 Cresswell to Amble

From Ellington we walked the mile to Cresswell where the official walk begins. I’m not sure why a barn owl would be hunting on Blakemoor Links on a bright morning but it was exciting to see. There we got onto the beach, shoes off, for the sunny miles of Druridge Bay. I don’t know the name for the long reach of water sloshing into a very shallow beach, but that’s the kind of sea it was. There is hardly anyone on these beaches – just enough so you don’t feel isolated. We passed East Chevington nature reserve, where the wildlife is currently persecuted by murderous vandals, stopping briefly to chat with a local gent who walked the same walk every day and admired the Montane walking t-shirt M’s mum had given him for his birthday. Nothing much for a vegan to eat at the Premier Stores in Ellington, but Matt had picked up a pasty and we still had a roll and some falafel left from yesterday so we ate those sitting on a bench looking at kayakers on the Ladyburn Lake at the Druridge Bay Country Park and talking to their grandma, followed by a coffee at the Visitors Centre. Then more dunes. We were too tired to follow Roland Tarr’s advice and look for birds at the Low Hauxley Nature Reserve and instead trudged on to Amble, a delightful town with port, River Coquet (another Norman name – pronounced caw-kit), beach and exciting wave-wracked jetty for our route into the town.

Though the stage ends at Warkworth further along, it has less accommodation and amenities so we stayed in Amble at the Wellwood, another Punch Tavern, and ate gaspacho, quinoa salad (me) and pizza (M) in the covered outside section of the Old Boathouse. After that we took another turn around the town where we saw surfers paddling home across the river mouth at dusk to save a two-mile walk. Then back at the Wellwood we watched the women’s Euros semi-finals where England won. Nice to see so many older gents and women watching together.

Day 4 Amble to Howick (Craster)

After a foray to the Co-op to pick up lunch (vegan luncheon meat, rolls, tomatoes, packet salad) we followed the river path into Warkworth and walked round the castle precinct then out to the golden sands of Alnmouth Bay. There I slipped and fell on some weedy rocks and was capsized like a beetle for some moments in fear that my pack would drag me over the edge. A mile of paddling through the flat ripples brought us to a turn in along the estuary through farmland. The long vistas made it seem as if we were approaching the bridge into Alnmouth for a lifetime. We ate our lunch in a play area built to celebrate the construction of the sea wall, then walked into the village. Alnmouth is the port for England’s breadbasket and has many historical granaries we didn’t see because we were hurrying to get to Howick early. Instead we climbed an unusually steep and wooded hill onto cliffs. I think around Seaton Point is where we saw huts and caravans scattered amongst the bracken, often with wetsuits hung outside. There were no amenities and it wasn’t marked as a caravan park, and if it was it was lovely because of the space between abodes. There was one more the next day with this sense of seclusion and peace.

The cliffs then descended into dunes and we rested on a bench at Boulmer before diverting along the parallel Cycle Route 1 track through Seahouses (a farm of limousin cows, not the famous town) to the turn into Howick, a beautiful hamlet of stone houses and cottages where we were spending the night, Craster being fully booked. After a hurried shower and change in the lovely Old Rectory B&B, we rushed (or rather lurched stiffly) out again to catch the final opening hour of Howick Hall with its gardens and arboretum. 30 minutes before last orders at the tea room we were grudgingly served drinks – in my case a pot of Russian caravan tea which I drank black and as quickly as I could, which on an empty stomach inevitably led to me nearly throwing up in the sensory garden. Sadly there was no time to properly see the arboretum but at least we dropped off our entry fee and contributed a little to reviving the place after Storm Arwen.

We walked back and then a further two miles along quiet roads to the Cottage Inn at Dunstan for dinner (potato skins and a very good chickpea curry). We walked back at dusk and I was wracked by aches (which I attributed to unfitness and falling over) and had to have a painkiller to sleep. None of these pains and aches are much bother to us as walkers – they’re to do with a sedentary lifestyle and our advancing age, we price them in and they lessen as our bodies get used to walking and carryng our packs.

The Old Rectory has three downstairs rooms that guests can use and an honesty bar which M used. You can clearly hear the sea, and see it from some windows too. Howick Hall and two pubs within walking distances make it a good location, and it was the best accommodation we had, at a comparative price to everywhere else.

Day 5 Howick to Seahouses

The Old Rectory are competent with a vegan breakfast. We took the coast path into Craster, passing a colony of kittiwakes on the hexagons of the igneous whin sill (hard, flat outcrop) of Cullernose point. As well as their rather winning calls, which resemble whining and whinging, we could also detect the vast amounts of bird crap presumably falling into each other’s nests and spreading the awful avian flu. Flu has made a graveyard of Coquet and Farne islands, where where the seabird population has fallen by over 1%, also devastating the rangers and ornithologists who have been striving to nurture their habitat and increase their numbers. The blunt truth is that intensive farming of chickens is to blame, along with the generally hostile environment that oblivious humans create. Those chickens are coming home to roost now. I sense we are going to change our ways.

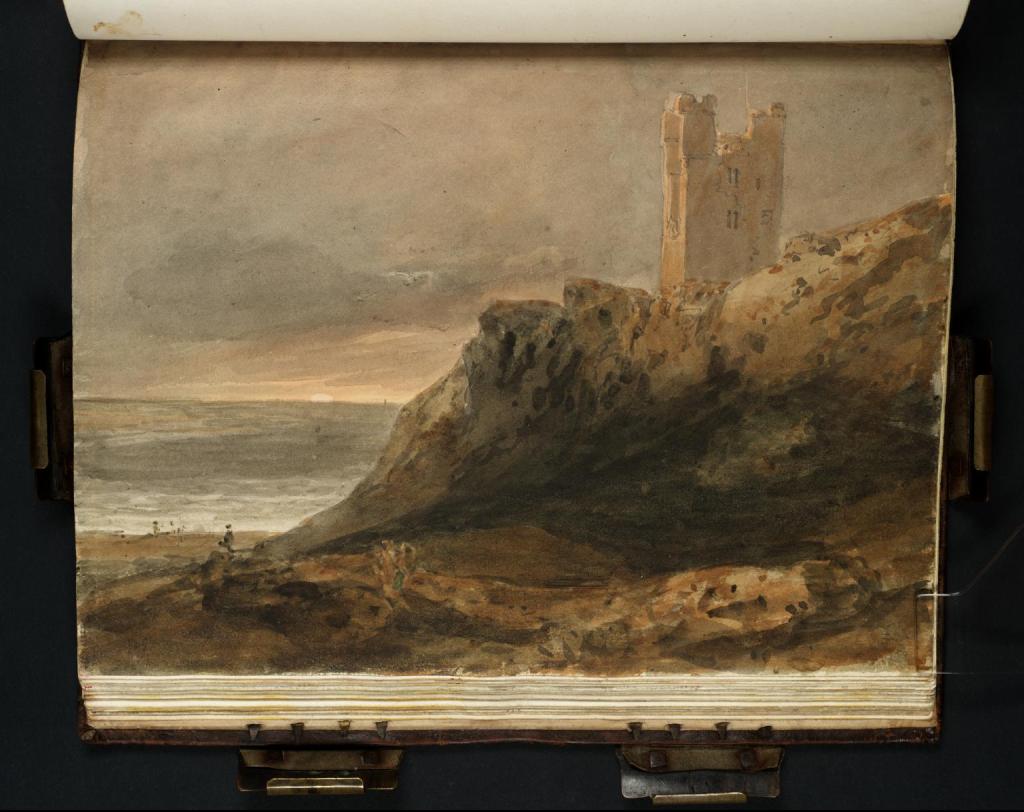

It was misty in Craster and the famous smokery hadn’t opened for the day so I didn’t get to risk their contempt by asking whether they smoke any plant foods yet. We set out along a lovely turf track towards the ruins of Dunstanburgh Castle with sea shore covered in boulders at low tide. My aches were receding.

We rounded the back of the castle, noticing the interesting Grey Mare Rock, and through the Dunstanburgh Castle golf club where we stopped for a drink at the club house. Like several along the route (and in fact I have never seen so many golf clubs on one walk) it welcomes non-members in a genuinely friendly way. This was one of many places we passed which was struggling to recruit and staffed by inexperienced though well-meaning workers – we noticed along the way that we were often served by mature or grandma-aged women instead of the younger Eastern European staff we’d have expected before Brexit. I overheard a conversation in the kitchen about everybody needing to muck in with the washing up in the absence of a hoped-for young person on school holidays. At around 12.30 we arrived at the hamlet of Low Newton-by-the-Sea with its gorgeous (and short-staffed) Ship Inn in a car-free grassy square overlooking the sea. The women who staffed it, some of whom looked as if they should have been putting their feet up in life, did extremely well. A compact bar and focused menu kept the encounters brief. You queued in one line for the bar and to order food, you got served with good humour, you paid and sat down, and then before very long your food was brought (two vegan options – I had a spiced cauliflower pie). Lovely little place and we also were fortunate to find exactly the right table for two with bulky packs.

It became sunny as we walked along the beach towards Benthall and Beadnell. I accidentally lowered myself onto a thorny rose bush while trying to pee discreetly and in haste among the dunes. The main thing I noticed about Benthall and Beadnell was the presence of what I’d call ‘Hainault houses’ – plain three-bedroom terraced or semi-detached homes that looked as if they’d been built for people of modest means in the 50s or 60s – found all along this coast on the sea front or clifftops with uninterrupted sea views.

We were pretty tired by the time we got to Seahouses, and Seahouses didn’t much revive us. I couldn’t see the charm and the Bamburgh Castle Inn where we stayed was somehow depressing. It might have been the terrible carpets in the hallways, or the gloomy cave-like bar area snubbing the sea views, or the extremely high prices. The town itself was full of holiday makers eating and drinking or looking for places to eat or drink – huge fish and chip barns abounded. After trying all other options (including a windowless room in The Ship and failing to get served at all in the Black Swan where the inattention of the young men staffing it belied their smart uniforms) we were obliged to eat at the Bamburgh as well as stay there. They had run out of some vegan options and M’s meal was particularly awful – the chickpea patties were rehydrated badly cooked falafel mix (were they averse to the word ‘falafel’ even though all vegetarians know what they are?) dried out rice and a poorly-flavoured sauce. I should say the service was competent and the room, clean and comfortable.

Day 6 Seahouses to Belford

That morning at Seahouses we bought another Co-op lunch of Quorn chicken slices, rolls and salad and set out along another uplifting sun-drenched beach, passing in front of the magnificent Bamburgh Castle on the sea shore with the village behind it. The castle is now owned by a scion of the Newcastle engineer and ship-builder George Armstrong. The local golf course did not welcome non-members so we walked on. The official path turns inland at this point because the coast around Lindisfarne is reserved for animal life, or perhaps holiness. Roland Tarr has struggled in mud on this inland section and invites you to take the coast path as far as possible and then get a bus. But since it had been dry we decided to take the official route. We had our lunch with our backs against a hay bale looking out at Bamburgh castle and Lindisfarne.

There were two other things Roland Tarr cautioned about. The first was having to cross the fast train track between Edinburgh and London. Indeed if we hadn’t phoned the signal office as directed, we would have had a close shave at best with a speeding LNER train. So do do that.

The next obstacle was the A1, which we crossed without incident. We then passed behind one of the several grain silos in the region and I thought of Ukraine. Most places we went we saw at least one flag – and it is also the colour of the sand against the sea and sky.

Belford has an intriguing calendar of cultural events. The teachers’ protest was not local trade unionism in action, but Norwegians standing up to that reliable old enemy the Nazis. This part of the country tends Conservative, English and Brexit.

The Blue Bell Inn is a historical coaching inn with a ballroom. It relieved us of nearly £130 in return for a room which was definitely not “well-appointed”. We had a badly-sprung bed, drabness, stains and and scuffs, poor upkeep and unwelcoming (perhaps demoralised) staff. Again, maybe somebody might take us for mucky itinerants with low standards who deserve poor accommodation, but if so they shouldn’t be working in hospitality. We weren’t offered vegan food and we weren’t offered breakfast in time to catch the tide and get to Lindisfarne. I hope somebody rescues this lovely old coaching inn from its current owners. For now I can say the Blue Bell was at least clean and we had a good view of the rolling hills. Things looked up after that. We took a turn round the village including the lovely old church and burial ground. The Salmon Inn is a fine pub and we got a good meal in the restaurant of the Sunnyhills Farm Shop which serves dinner and drinks to the nearby caravan site residents and is generally lovely. We got an apple pie from Belford Co-op for next day’s breakfast, along with the usual lunch.

Day 7 Belford to Lindisfarne, then Lowick

We left slightly before 8 to get the bus to a stop on the A1 for Fenwick, allowing us to walk through fields to access Lindisfarne by crossing three miles of intertidal zone. We encountered a frantic ewe calling for her lamb the other side of a barbed wire fence but also just a few metres from an open gate between the two fields. Seeing us she panicked and summoning all her strength, tried unsuccessfully to leap through the fence. It was quite hard to watch. I think we may have seen her in the same place the following day.

Arriving at the coast we had a decision to make. We hadn’t been sure whether we’d walk along the causeway road or the Pilgrim’s Way across the sand and mud. Official guidance, including Roland Tarr, cautions against the latter, but it is well marked and we took courage from some fresh footprints we could see striking out towards the first marker. I took off my sandals and went barefoot as advised in the pub. That crossing would have been the highlight of our trip even if half way across we hadn’t heard, and then seen, about 150 seals across the sands, raising their voices in a haunting song like a huge holy choir.

The barnacles on the posts went up to around my underarms but sometimes the tides would go over my head. The most important thing is to consult advice about tides for walkers rather than for vehicles. Also important, expect to make fairly slow progress, stick close to the markers and be prepared to get wet and muddy, perhaps to the knee – we saw a wellington boot stuck in the mud nearly to the top and I’d want to do this barefoot in warm weather. Walking poles are useful here, particularly on a stretch of slippery clay close to the start – we have packs and if we fall we go down like a tonne of bricks so we pick our way carefully.

At Lindisfarne we stopped for a coffee and half a bit of cake at Pilgrims Cafe, a walled garden where the sparrows will take crumbs from your outstretched hand. We then had time to see one thing, so on Roland Tarr’s suggestion we went to the Heritage Centre. There we interacted with digital Lindisfarne Gospels and watched some awe inspiring videos of how such a book would have been constructed and illuminated. We listened to different bird calls, and there was an illustrated interactive exhibit where you could ‘meet’ some residents of the island by selecting from a menu of questions to ask them (such as ‘Have you ever been stranded?’) which would then activate the relevant recorded answer. I particularly liked that ‘Goodbye’ was on the menu – the farewells were all differently cordial and you really did feel that you’d approximately met your hosts on the island. Another great recommendation from Roland Tarr. By that time I’d come to trust him implicitly.

We had to get back and walked to the bus stop in the village carpark. A bus from Berwick arrived and a young man of perhaps 17 got off. We weren’t sure whether to get on that bus, but he authoritatively advised against it and pronounced our bus due in minutes. He kept lookout along the lane, ascertained its whereabouts and conscientiously updated us. When it arrived he photographed it and got straight on to leave the island. Being the only three passengers I was able to indulge my curiosity. It turned out he was an ardent bus spotter, having converted from trains during the Covid-19 pandemic. He used his free time to make as many journeys by bus as possible. Lindisfarne had been a diversion for him, an unforeseen chance to be on two new buses discovered only that morning after setting off on a circuit which would take in Berwick and Newcastle before returning home to County Durham that night. Definitively not a tourist, with the single-mindedness of (I am assuming) neurodiversity he wouldn’t stop off anywhere unless timetabling necessitated it – and as a bustimes.org user he had no inclination to visit London because he said his searches crashed the site.

We got off back at the A1 and had an unmemorable, expensive lunch at the Lindisfarne Inn (same chain as the not-nice Bamburgh Castle but more welcoming). Then we walked 2.5 more miles inland with views of the Cheviots to Lowick House, a very well-run airbnb accommodation a pleasant walk from the village of Lowick. This was another highlight because the place was so well-kept, the room was comfortable, and the hosts were very helpful and warm. That evening we walked through a farm and along a quiet road to the Black Bull in Lowick and had a very good vegan meal – generous filo case filled with leek, chestnuts and artichoke – in lovely surroundings. We walked back at dusk, diverting into a playground to see the beautiful skies. Night falls later up there; this was close to 10pm on the last day of July.

Day 7 Lowick to Berwick-upon-Tweed

This would be the last day of our walk. It felt like a long slog back to the Lindisfarne causeway to pick up the coast path again. I hope somebody buys the old granary with the many dovecotes at Fenwick and saves it from ruin. The fast rail crossing had been blocked for weeks or months and diverted a couple of kilometres to a bridge. There was a Samaritans notice hinting at why. On the sea shore we turned north along some of the old World War Two defences, briefly inland to cross a river, then back again. The area around Goswick was throught to be particularly vulnerable because of the nearby railway line so they did belt and braces – there are dragons teeth, pillboxes, gun emplacements, tank traps, anti-glider poles and lookout towers, and hopefully no more landmines. We had lunch in Goswick Golf Club (jacket potato and baked beans for vegans) and noticed the accents had become mostly Scottish. Then back onto dunes (I saw a little weasle) then fields and an exciting nature reserve with beach users at Cocklawburn (not Norman but don’t pronounce the ‘ck’) where we watched raptors hover for bunnies who only came out when they flew away. There were many cows and calves, including a youngster which had managed to get himself stuck between the barbed wire fence erected to protect the dry stone wall and the wall itself. We lifted the wire and nudged the calf but he seemed depressed and entirely lacking the will to save himself. As he wandered free with his head low, nobody acknowledged him and it was clear he was abandoned by his mother and a lonely outcast of the herd.

We reached Spittal with its fine promenade, then turned into Tweedmouth where swans – whose moult leaves them flightless at this time of year – watched men load trees on a ship.

Then we wearily crossed old bridge into Berwick and arrived at the splendid YHA Berwick in a rescued granary just back from the quay. We had a private room with a bunk, a toilet and separate wetroom so we showered, changed and rested briefly after 17 long miles. After a wander round the town we went to catch the Euro final in the Brown Bear and were able to see Germany’s equaliser and Chloe Kelly’s winning goal. We ate good Turkish food at Mavi, watched some of the Commonwealth games back at the youth hostel and went to bed.

A day in Berwick

After breakfast at the youth hostel we locked our bags in its bike shed and set off following Roland Tarr’s suggested circular tour round the mediaeval and Elizabethan walls, which was fascinating and brought alive with plenty of interpretation boards.

Berwick was contested and fortified to the hilt until relatively recently, and at one time had changed hands (between the English and Scots) more than any other place in Europe. Roland Tarr recommended the museums at Berwick Barracks so we went there. First we learned about the history of soldiering through the ages in 12 curated rooms. Most of Britain’s wars were against the French and even the American war of independence was lost because the French intervened for the American rebels. Soldiers were sent to fight in stupid, impractical uniforms (an early iteration of the tommy, ‘Tommy Lobster’ refers to the red coats you read about in Jane Austen novels) which they had to pay for themselves. They had badly designed equipment like the smart-looking back pack which cut off their blood supply and some ridiculous quilted hats worn in India. When sent overseas in the 1700s and 1800s many died on the way but they liked to go to America because the prospects for desertion were good.

I hadn’t realised that barracks were a relatively recent innovation because residents and innkeepers hated being forced to billet soldiers. Almost all were illiterate and were not allowed to marry; consequently the main passtimes were drinking, brawling and gambling. A soldier’s life was certainly cheap – you signed up for life and various stoppages were deducted from your promised wage so that you had very little left for any quality of life, let alone to save up. Soldiers would frequently seek oblivion in cheap spirits rather than feed themselves and consequently were in poor health. Hardly any could read, one in four would be punished for some transgression and many were badly injured by their punishment. There’s more to say about how the British army gained its formidable reputation but my hunch is that very few readers are sticking with me by now – so I recommend going and seeing for yourself.

Also in the barracks, the Berwick Museum and the Burrell Collection are both excellent. I’d have liked to stay longer but we had to have lunch (at the Corner House Cafe which is very veggie friendly) before catching the train back to London at 3.13. The journey was peaceful as it often is at that time of day, and we had dinner at the lovely Namaste Holborn before taking the hot but relatively calm Central Line back home. There we found the aubergines, parsley, french beans, cabbages, broccoli, chillis and tomatoes alive and well and nothing burgled or burned down.

What a marvellous week.